At present, the United States is facing significant geopolitical challenges in three separate regions, involving three major global players, while advocating for the interests of three nations that do not have formal treaties with the United States.

Despite the recent temporary truce and hostage deal announced on Tuesday, US forces remain present in the Middle East as a deterrent against Iran and Hezbollah getting involved in Israel’s conflict with Hamas. This presence puts American troops at risk and raises the potential for the US to become entangled in another major conflict in the region. American forces have already faced numerous drone and missile attacks from Iranian-backed groups in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, leading to retaliatory strikes. Additionally, in Eastern Europe, the US is effectively engaged in a proxy war with Russia over the situation in Ukraine, and in East Asia, there’s a risk of a significant confrontation with China regarding the political status of Taiwan.

President Joe Biden has framed these situations as part of a global struggle between democracy and autocracy, emphasizing America’s role as the “indispensable nation.” He argues that US leadership is essential for the success of countries like Israel and Ukraine, asserting that the US is “the essential nation.”

However, these claims are subject to scrutiny. Many believe that the US’s involvement in these crises is stretching its capabilities, increasing risks, fueling local conflicts, and diverting resources that could be better used domestically. Recent polls show declining support among both Democrats and Republicans for military aid to Israel and Ukraine. The longstanding US policy of maintaining allies and adversaries in the Middle East has often been counterproductive to its goal of regional stability. For instance, the US’s actions, such as economic sanctions on Iran and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s government in Iraq, inadvertently boosted Iran’s regional influence, leading to unintended consequences.

Moreover, regional stability has not been improved by the actions of the United States’ partners, who have often engaged in troubling behavior enabled by Washington’s unconditional support. The US has consistently supported Israel, even in the face of its ongoing construction of settlements in the occupied West Bank and the enduring blockade of Gaza. These actions have exacerbated the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which now poses a significant threat to the entire region.

Additionally, despite the US’s rhetoric about promoting democracy over autocracy, it backed Saudi Arabia’s brutal campaign against the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen. This conflict has resulted in what the United Nations described as “the worst humanitarian crisis in the world,” with hundreds of thousands of casualties and a large portion of the population in dire need of humanitarian aid. Surprisingly, the Biden administration has strengthened its security ties with Saudi Arabia despite these concerns.

Contrary to the goal of avoiding broader conflicts in the Middle East or Ukraine, President Biden’s recent Oval Office address attempted to frame these crises as global issues. He argued that if the US doesn’t deter distant adversaries, they will become emboldened to pursue further aggression, ultimately undermining American alliances. However, these arguments are based on questionable assumptions drawn from historical events such as World War II (the “Munich analogy”) and the Cold War (the “domino theory”).

For example, Biden suggested that if Russia is not stopped in Ukraine, Vladimir Putin would continue to expand into countries like Poland or the Baltic states. This scenario is not seen as plausible by many experts. Russia lacks the material capacity to attempt to conquer Eastern Europe, even if it had the desire to do so. European NATO members in 2022 spent significantly more on defense, had a larger GDP, a much larger population, and their own nuclear deterrent, making such fears less likely. Russia’s struggles in Ukraine further diminish the credibility of this concern.

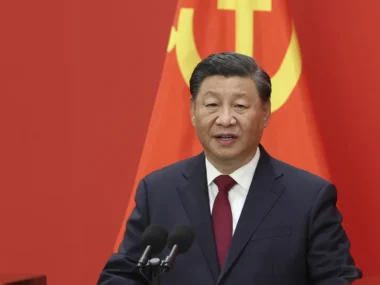

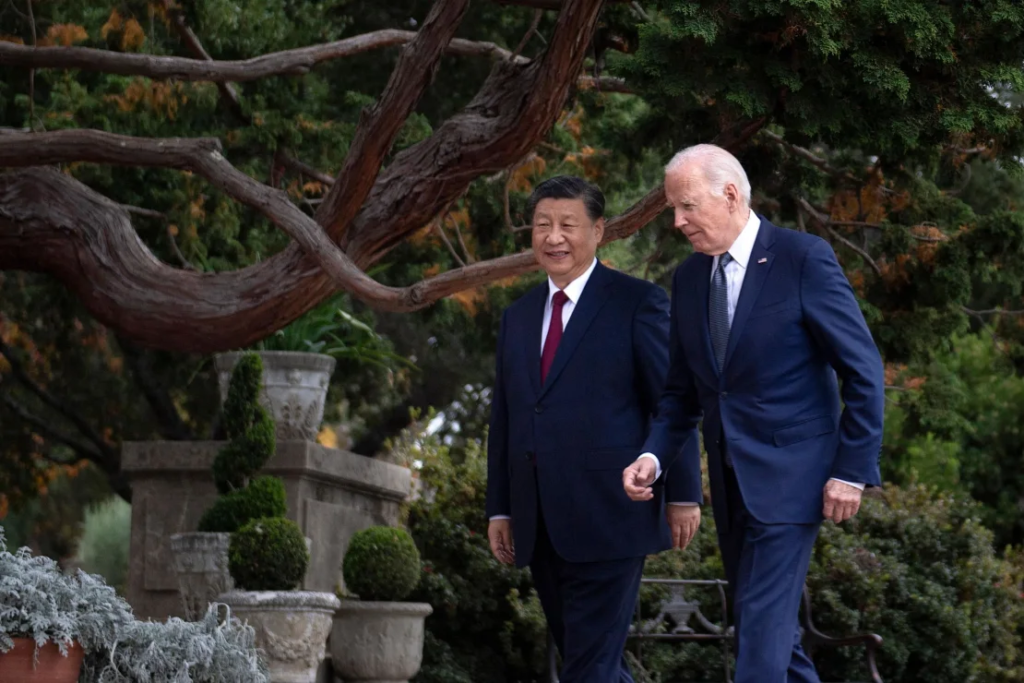

President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping met during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders’ week in California on November 15. Biden praised the discussions with Xi, highlighting that agreements were reached on issues related to fentanyl and military communication.

Furthermore, the President also hinted that if Russia is not decisively defeated in Ukraine, it could embolden China to take action in Taiwan. However, this assumption lacks a solid foundation. Political scientists like Daryl Press and Jonathan Mercer argue that states tend to assess their adversaries’ future actions based on their current capabilities and perceived interests, rather than past behavior in unrelated contexts. If China were to consider invading Taiwan, it would likely be due to Beijing’s stronger stake in Taiwan compared to Washington, its military advantage in the vicinity, and a belief that peaceful reunification is no longer feasible. It would not primarily result from a perceived wavering of US support for Ukraine.

Moreover, there is no indication that America’s treaty allies doubt the credibility of the US commitment to their defense. The relatively low defense spending by capable states like Japan and Germany suggests that these allies still have confidence in relying on the United States for their security. If the US were to reduce its defense commitments, it is highly probable that Japan and Germany would increase their own defense efforts out of their inherent need for self-preservation. This doesn’t imply that they would simply cede their sovereignty to China or Russia.

In light of these considerations, it is suggested that the US should adopt a more restrained grand strategy. Such a strategy would involve setting clearer priorities among its foreign interests, reducing the risk of getting entangled in conflicts, minimizing the provocation of distant rivals, and aligning more closely with America’s domestic resources and requirements.

As former President Richard Nixon aptly stated, “Our interests must shape our commitments, rather than the other way around.”

The first key principle is that the United States should avoid maintaining permanent allies and adversaries. As former President Richard Nixon wisely articulated, “Our interests must shape our commitments, rather than the other way around.” Military alliances, by their nature, entail commitments to potentially engage in armed conflict on behalf of others. Therefore, the US should form alliances in response to specific threats as they arise, adapting these alliances as the nature of threats evolves. It’s crucial that alliances are driven by genuinely vital security interests rather than aspirations of global leadership, considering the significant costs and risks involved.

The second principle advocates that the United States should refrain from inadvertently uniting its adversaries. By framing international politics as a dichotomy between democracy and autocracy, the US risks generating a multitude of adversaries. The increasing alignment of security interests among countries like China, Russia, and Iran is primarily a response to a common perceived threat from the United States, rather than a shared goal of promoting a particular type of regime (which they do not hold in common). It’s worth noting that the US itself has a significant history of attempting to impose its own values on others through military force. Prudent efforts to reconcile with former adversaries should be pursued when there are no critical interests in contention.

The third principle suggests that the United States should transition the responsibility for managing regional threats to its regional partners, particularly in areas like the Middle East and Europe. This shift is prompted by the realization that America’s resources are finite, as demonstrated by ammunition shortages resulting from conflicts such as those in Ukraine and Gaza. By empowering and encouraging regional partners to take on a more substantial role in their own security, the US can alleviate some of the burdens it currently shoulders.

The final principle emphasizes that by reducing its overextended military presence, the United States can encourage capable regional states with a vested interest in self-preservation to collaborate and counterbalance local threats on their own. Shifting the burden of security to regional partners would not only help avoid the risk of the US being drawn into major wars but also cut down on the substantial expenses associated with maintaining military forces overseas. The United States, with its favorable power position and geographical distance from Eurasia, has the luxury of delegating more responsibility to others while still maintaining its own security.

Lastly, if the US aims to promote democratic values worldwide, it should do so by serving as a compelling model of a successful democracy at home, one that others would want to emulate. President Biden often speaks of America as a beacon to the world. However, as the US grapples with the challenges of sustaining its global empire, its own democratic republic faces internal issues. This principle suggests that it is essential to prioritize the well-being of the republic itself rather than focusing primarily on sustaining the empire.