A groundbreaking tunnel is currently being constructed beneath the Baltic Sea to connect Denmark and Germany, aiming to significantly reduce travel time and strengthen Scandinavia’s connection to mainland Europe.

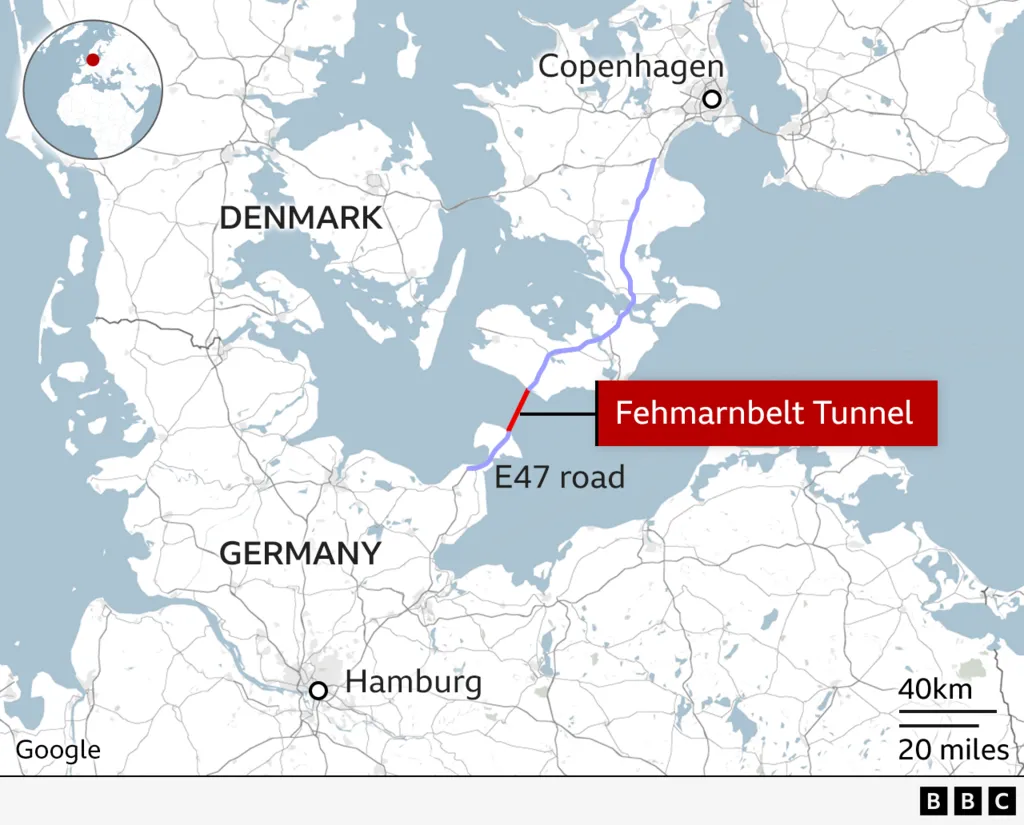

Known as the Fehmarnbelt, the 18km (11-mile) structure will become the world’s longest submerged tunnel designed for both road and rail traffic using pre-fabricated components.

This massive engineering project involves placing large tunnel segments directly onto the seabed and joining them together.

Construction is centered at the northern end of the tunnel, on the coast of Denmark’s Lolland island. The site spans over 500 hectares (1,235 acres) and includes both a harbour and a specialized factory producing the tunnel’s structural components, referred to as “elements.”

Each element measures 217 meters (712 feet) in length and 42 meters in width, made by pouring concrete around reinforced steel.

Unlike most underwater tunnels—such as the 50km Channel Tunnel between the UK and France, which was drilled through bedrock—this one will be assembled from 90 prefabricated segments, linked together much like Lego pieces.

“We’re setting new benchmarks with this project,” said Henrik Vincentsen, CEO of Femern, the Danish state-owned company behind the tunnel. “Immersed tunnels aren’t new, but nothing has been done at this scale before.”

The 18km road and rail tunnel connecting Denmark and Germany will feature five parallel tunnel tubes.

With an estimated cost of €7.4 billion ($8.1 billion; £6.3 billion), the project is primarily funded by Denmark, with €1.3 billion contributed by the European Commission.

It ranks among the largest infrastructure undertakings in the region and supports the EU’s broader goal of enhancing continental connectivity while lowering reliance on air travel.

Once operational, the Fehmarnbelt tunnel will reduce the travel time between Rødbyhavn in Denmark and Puttgarten in Germany to just 10 minutes by car and seven minutes by train—replacing the current 45-minute ferry trip.

The new rail link will also bypass western Denmark, cutting the Copenhagen–Hamburg journey from five hours to 2.5. This provides a faster and more environmentally friendly route for both passengers and freight.

“It’s not just a connection between Denmark and Germany,” says Henrik Vincentsen. “It links all of Scandinavia with central Europe.” He adds, “Everyone benefits. By cutting travel by 160km, we’re also cutting emissions and easing the environmental burden of transport.”

Massive cranes dominate the tunnel entrance, which is set against a steep coastal wall beneath the clear waters of the Baltic Sea.

“We’re now entering the first section of the tunnel,” says Anders Gert Wede, senior construction manager, while walking through what will become a highway. Each tunnel element contains five parallel tubes.

Two are designated for rail, two for road traffic—with two lanes in each direction—and the fifth is reserved for maintenance and emergency access.

At the far end, large steel gates currently hold back the sea. “As you can hear, it’s very solid,” Wede says, tapping the thick metal. “Once an element is completed at the harbour, it’s towed into position and gradually lowered behind these doors.”

These segments are not only long but extremely heavy—over 73,000 tonnes each. Yet, by sealing the ends and equipping them with ballast tanks, they become buoyant enough to be towed by tugboats.

Placing each one is a meticulous operation. Using underwater cameras and GPS-guided systems, crews lower the elements 40 meters into a seabed trench, aligning them with just 15mm of tolerance.

“We must be extremely precise,” Wede explains. “We use a ‘pin and catch’ mechanism—basically a V-shaped guide with arms that slowly pull the segment into its exact position.”

The tunnel is being built from north to south, via a construction facility around its northern entrance

Denmark lies at the entrance to the Baltic Sea, an area crisscrossed by major shipping routes.

According to Professor Per Goltermann from the Technical University of Denmark, the subsoil—composed of clay and chalk—was too soft for traditional tunnel boring methods. Initially, a bridge was considered, but strong winds posed risks to traffic flow, and the potential for ships colliding with bridge structures raised safety concerns.

“While we could design a bridge to withstand such impacts, the depth of the water and size of vessels using this route made it problematic,” Goltermann noted. This led to the decision to construct an immersed tunnel instead. “They assessed the options and found the tunnel to be both the safest and most cost-effective solution.”

Although Denmark and Germany agreed to the tunnel project back in 2008, progress was delayed due to objections from ferry companies and environmental groups in Germany. One such group, Nabu, raised concerns about the tunnel’s impact on local marine ecosystems, particularly larval habitats and harbour porpoises, which are highly sensitive to underwater noise.

However, in 2020 a federal court in Germany dismissed the legal challenge, allowing construction to proceed.

Henrik Vincentsen, CEO of Femern, emphasized that extensive efforts have been made to minimize environmental harm. This includes the development of a 300-hectare wetland and recreation zone, created using material excavated during construction.

The tunnel is scheduled to open in 2029, and Femern projects it will handle more than 100 trains and 12,000 vehicles daily. Revenue from toll fees is expected to repay the government-backed loans over approximately 40 years. “In the end, users will cover the cost,” Vincentsen said.

Beyond improving transport links, the project is also expected to stimulate economic growth in Lolland—one of Denmark’s less affluent regions. “The community has waited a long time for this,” said Wede, who is originally from the area. “They’re eager to see new businesses arrive.”