The issue draws a sharp divide between left and right, with populists appealing to voters by promising to abolish the levy.

The Norwegian general election has been ignited by a heated debate over the national wealth tax: whether it should be retained, reduced, or abolished. As voters prepare to head to the polls on Monday, the issue has sparked a fierce national discussion that is likely to continue regardless of the election outcome.

In Norway, a country with an economy less than one-seventh the size of Britain’s, the wealth tax—known locally as the formuesskatt—generates around 32 billion kroner (£2.4bn). By comparison, applying the same rules in the UK could raise over £17bn, highlighting the tax’s financial significance. Supporters argue that the levy is a cornerstone of Norway’s progressive tax system, contributing to one of the most equal societies in Europe.

However, entrepreneurs are pushing back, funding lobbying campaigns, investing in political advertising, and even producing protest songs. One LinkedIn video features a business consultant singing: “Don’t come to Norway, we will tax you till you’re poor, and when you have nothing left, we will tax you a little more.” Meanwhile, Socialist Left party leader has created a “wall of shame” in her office listing those who oppose or avoid the tax.

Experts advising on the issue are also facing backlash. Economists and statisticians have been targeted with disinformation campaigns, hate mail, and negative coverage in the press. Annette Alstadsæter, director of the Skatterforsk Centre for Tax Research at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, has publicly supported the tax and authored research on avoidance and offshore wealth. She has since become cautious about public statements and withdrawn from social media due to online abuse. “People are so angry. Either you are very against or very for,” she said.

Economist Mathilde Fasting, a member of the right-leaning think tank Civita and advocate for abolishing the tax, noted that the debate has reached unprecedented levels of intensity. “I’ve been working on this for 15 years and it’s always been an issue, but this time it has exploded,” she said. “Every discussion of economic matters brings this tax up. It’s like a symbol of everything else happening.”

In a nation where politics traditionally lean toward the center, the wealth tax has created a stark divide between left and right. The controversy has evolved into a broader culture war, with populist appeals aimed at young, aspirational men who may not yet be subject to the levy but oppose it on principle. On the YouTube show Gutta (Guys), four muscular hosts poured champagne over their wristwatches while discussing “tax refugees,” further fueling the debate.

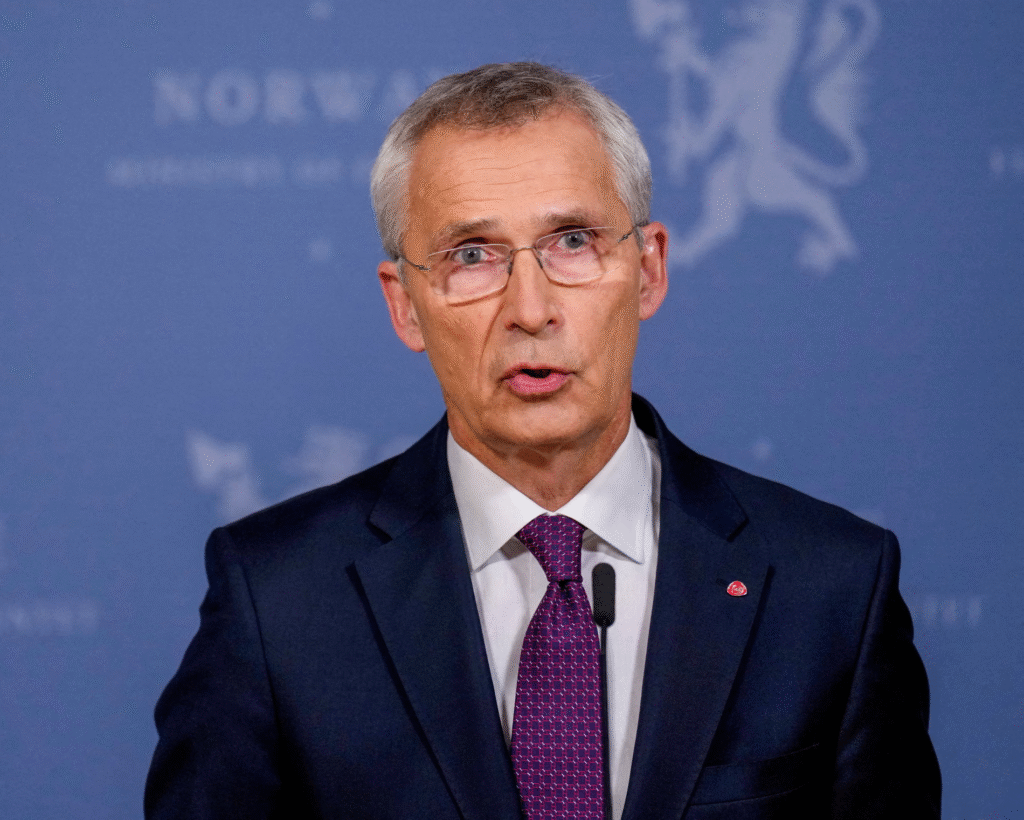

Jens Stoltenberg has pledged to establish a cross-party panel to review all taxes if Labour wins the election.

Jens Stoltenberg, former NATO Secretary General and ex-Norwegian prime minister, who returned to frontline politics in February as finance minister, has promised to form a cross-party commission to review all taxes if Labour regains power. Thanks to his broad appeal, Labour has climbed in the polls, now ahead of the populist Progress Party, which has pledged to abolish the wealth tax (formuesskatt). The more moderate centre-right Høyre party, in third place, wants to significantly reduce the amount collected.

During his decade leading NATO, Stoltenberg earned the nickname “the Trump whisperer” for persuading President Trump not to withdraw from the alliance in his first term. Applying those diplomatic skills may be necessary again to navigate the wealth tax debate, as the challenge is to maintain the tax without prompting a flight of billionaires.

“If a ton of people leave Norway that would be a problem,” said entrepreneur Karl Munthe-Kaas, a supporter of the tax. “But if we let these groups that have all this money hold the rest of the country hostage, I have an issue with that.”

Beneath the heated rhetoric, Norway’s tax discussion is remarkably informed and nuanced. Citizens engage confidently because they have access to comprehensive, publicly available data. Individual tax returns are transparent, and company information is detailed and reliable—an unusual level of openness among democracies.

Norway has taxed wealth above a certain threshold since 1892, even before achieving full independence from Sweden. Alongside Spain and Switzerland, it is one of only three European countries still levying such a tax. The current rates are 1% for assets over 1.7 million kroner (£125,000) and 1.1% for assets exceeding 20.7 million kroner. The tax is assessed annually, covering property, savings, investments, and shares, minus any debts. Private companies are included in owners’ wealth calculations, though some discounts apply—for example, only 25% of a primary residence’s value is taxable.

Norway is among just three European countries that impose a tax on high-value wealth.

While 720,000 Norwegians pay the wealth tax, most contribute only modest amounts annually. Economist Mathilde Fasting notes that around 3,000 individuals have taxable assets exceeding 100 million kroner.

Among the largest payers is Gustav Magnar Witzøe, heir to the SalMar fish farming business. In 2023, he paid 330 million kroner in wealth tax, reportedly his only personal tax due to having no income. Under proposals from the centre-right Høyre party, his bill could fall to zero, as the party wants to exclude “working capital”—assets tied to active businesses.

Reforms introduced by Labour have increased total wealth tax revenue from 18 billion kroner in 2021 to 32 billion kroner last year, with estimates for 2025 even higher. The 2022 changes prompted the departure of more than 30 billionaires and multimillionaires, including industrialist Kjell Inge Røkke, Norway’s fourth richest person, who moved to Switzerland. Despite fears of lost revenue and economic harm, the exodus appears to have had limited impact.

Norwegian billionaires continue to grow wealthier. In 2024, the country’s 400 wealthiest individuals were worth 2.139 trillion kroner, a 14% increase over the year, though half of that wealth is now held by families living abroad. Fasting expects more to leave, arguing that taxes discourage investment, company listings, and entrepreneurship. “If Labour remains in power, you will see a boost of people moving,” she says.

Critics contend the wealth tax puts Norwegian entrepreneurs at a disadvantage compared with foreign company owners, who face fewer restrictions. One prominent lobby group, Aksjon for Norsk Eierskap (Action for Norwegian Ownership), includes backers such as salmon exporter Roger Hofseth. Hofseth warned recently that a Labour victory could trigger further departures to Switzerland.

Supporters emphasize fairness and shared responsibility. Annette Alstadsæter of the Centre for Tax Research stresses that even self-made wealth depends on public goods like education, healthcare, and social security, and that everyone should contribute. Some adjustments are suggested, such as raising the taxable threshold above 1.7 million kroner.

Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, funded by oil and gas revenues, contributes roughly 25% of public spending, yet many argue that the formuesskatt is still important for equity. Simen Markussen, director of the Ragnar Frisch Centre for Economic Research, says the tax ensures capital owners without labor income pay a fair share and helps redistribute wealth. For the very wealthy, it often represents the bulk of their personal taxes. “Compared with all taxes on personal income it’s maybe 4.5%,” Markussen notes, “but it’s meaningful enough that politicians proposing its abolition should explain how they would replace the revenue.”

Entrepreneur Karl Munthe-Kaas, founder of Norway’s first “unicorn” startup Oda, believes the tax functions well and would favor cutting corporation tax instead. “The wealth tax is not a choice between value creation and redistribution—it delivers both,” he says. “Any tax reduces the ability to invest or consume, regardless of who pays it. Taxing the rich is no different than taxing a middle-class worker.”

Karl Munthe-Kaas, founder of the Oda grocery delivery startup, says the wealth tax is effective.

André Nilsen, a neuroscientist and millionaire thanks to family wealth and personal investments, pays only a small amount in wealth tax each year. He supports keeping the formuesskatt, arguing it helps fund social security. “It’s easier to become wealthy in Norway than in other countries. You can take risks and explore new ideas because there’s a safety net if things don’t work out,” he says.

While the wealthy often donate generously to charity, Nilsen believes philanthropy cannot replace taxes. “There must be a system above everyone that ensures at least this contribution,” he adds.

Other countries target wealth differently. For instance, the UK taxes dividends, capital gains, and inheritances, though rates are often lower than on wages and loopholes exist.

Annette Alstadsæter notes that Norway’s wealth tax is harder to avoid. “It’s the only tax that cannot be circumvented through restructuring while living in Norway, which explains much of the opposition,” she says.