Snow leopards don’t growl — instead, when you approach one, she might start purring.

One such leopard, named Lovely, was rescued as a cub 12 years ago in Gilgit-Baltistan, a region administered by Pakistan.

Raised in captivity and dependent on humans for food, she never learned how to hunt — making it impossible to release her back into the wild.

“If she were set free, she’d likely attack livestock and be killed,” explains her caretaker, Tehzeeb Hussain.

Although snow leopards are legally protected, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) reports that 221 to 450 are killed annually. This has led to a 20% global population drop in the last 20 years.

Over half of these killings are retaliatory — typically by farmers defending their animals.

Today, only an estimated 4,000 to 6,000 snow leopards remain in the wild. Around 300 of them live in Pakistan, home to the world’s third-largest population.

In response, WWF and Pakistan’s Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) have introduced AI-powered cameras designed to spot snow leopards and send villagers text alerts — giving them time to protect their livestock.

The cameras run on lithium batteries and are powered by solar panels.

Standing tall with a solar panel on top, the cameras are installed high in the harsh, rocky mountains at altitudes close to 3,000m (9,843ft).

“This is snow leopard territory,” says Asif Iqbal, a conservationist with WWF Pakistan. Taking a few more steps, he gestures at fresh tracks on the ground: “These are quite recent.”

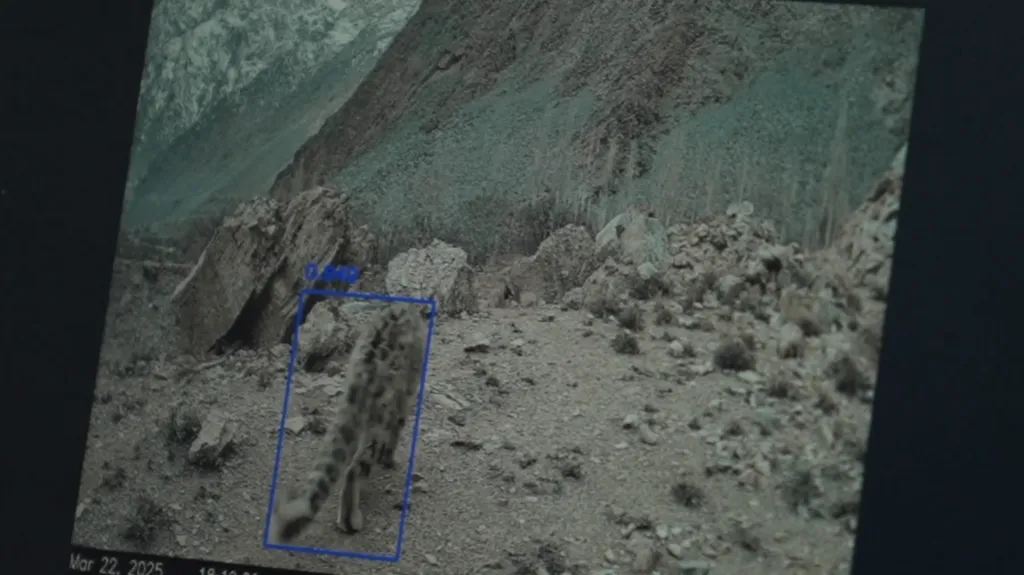

Asif is hopeful the camera has captured new footage, showing that the AI system — designed to distinguish between humans, other animals, and snow leopards — is functioning as intended.

Trial and error

WWF is currently piloting 10 AI-equipped cameras across three villages in Gilgit-Baltistan. It took three years to train the AI model to reliably identify humans, animals, and snow leopards — with strong, though not flawless, accuracy.

Back from the mountains, Asif opens his laptop and shows a dashboard. There I am, captured in several GIFs — correctly tagged as a human. As we scroll further, I appear again, but this time the system labels me as both human and animal. I’m wearing a thick white fleece, so I let it slide.

Then comes the highlight: a snow leopard caught on night-vision just a few nights ago. Asif also shows another clip from the previous week — a leopard raising its tail toward a rock. “She’s likely a mother, marking her territory,” he explains.

These cameras are designed to identify when a snow leopard is nearby and immediately alert villagers, so they can relocate their livestock to safety.

Installing the cameras in steep, high-altitude terrain involved extensive trial and error. WWF tested multiple battery types before finding one that could handle the extreme winter conditions. They also selected a special non-reflective paint to avoid startling passing wildlife.

If cellular signals drop in the mountains, the cameras still record and store data locally. However, the team acknowledges that certain challenges remain unavoidable.

Although the camera lens is shielded by a metal casing, solar panels have occasionally needed replacement after being damaged by landslides.

Doubt in the community

The issues haven’t only come from the technology itself—gaining support from the local community has been difficult as well. Initially, there was skepticism about whether the project would benefit either the people or the snow leopards.

“We found some wires cut,” Asif explains. “Blankets had been thrown over some cameras.”

The team also had to consider cultural sensitivities, particularly around women’s privacy. Certain cameras were relocated because women frequently used those paths.

Some villages still haven’t signed the required consent and privacy agreements, preventing the technology from being deployed there. WWF is seeking a firm commitment from local farmers not to allow poachers to access the footage.

Sitara mentions that a snow leopard attacked and killed one of her sheep while it was out grazing.

Sitara lost all six of her sheep in January. She explains that she had taken them to graze on land above her home when a snow leopard attacked them.

“It took three to four years of hard work to raise those animals, and it was all gone in one day,” she says.

The loss of her livelihood left her bedridden for several days. When asked if she believes the AI cameras might help in the future, she responds, “My phone barely gets any service during the day, how can a text help?”

At a gathering of village elders, leaders from Khyber village discuss how attitudes have shifted over time, with an increasing number of villagers recognizing the importance of snow leopards and their role in the ecosystem.

According to the WWF, snow leopards hunt ibex and blue sheep, preventing these animals from overgrazing and helping to maintain grasslands that villagers rely on to feed their livestock.

However, not everyone is convinced by this argument. One local farmer points out the negative impact snow leopards have had on his herd.

“We used to have 40 to 50 sheep, but now we only have four or five, and it’s because of the threat from snow leopards and ibex eating the grass,” he says.

Climate change also contributes to the tension between villagers and snow leopards. Scientists suggest that rising temperatures have forced villagers to move their crops and livestock to higher ground, encroaching on the snow leopards’ habitat and making livestock more vulnerable to attacks.

While the villagers’ acceptance of conservation efforts remains uncertain, the WWF notes that legal consequences have acted as a strong deterrent. In 2020, three men were imprisoned for killing a snow leopard in Hoper Valley, located about two hours from Khyber. One of the men had shared photos of himself with the dead animal on social media.

Though the team behind the camera project remains optimistic about its potential impact, they acknowledge that these devices alone won’t solve the problem.

Starting in September, they plan to test a combination of smells, sounds, and lights at camera sites to discourage snow leopards from entering nearby villages, thereby protecting both the animals and local livestock.

Their work tracking these elusive creatures, the “ghosts of the mountains,” is far from finished.