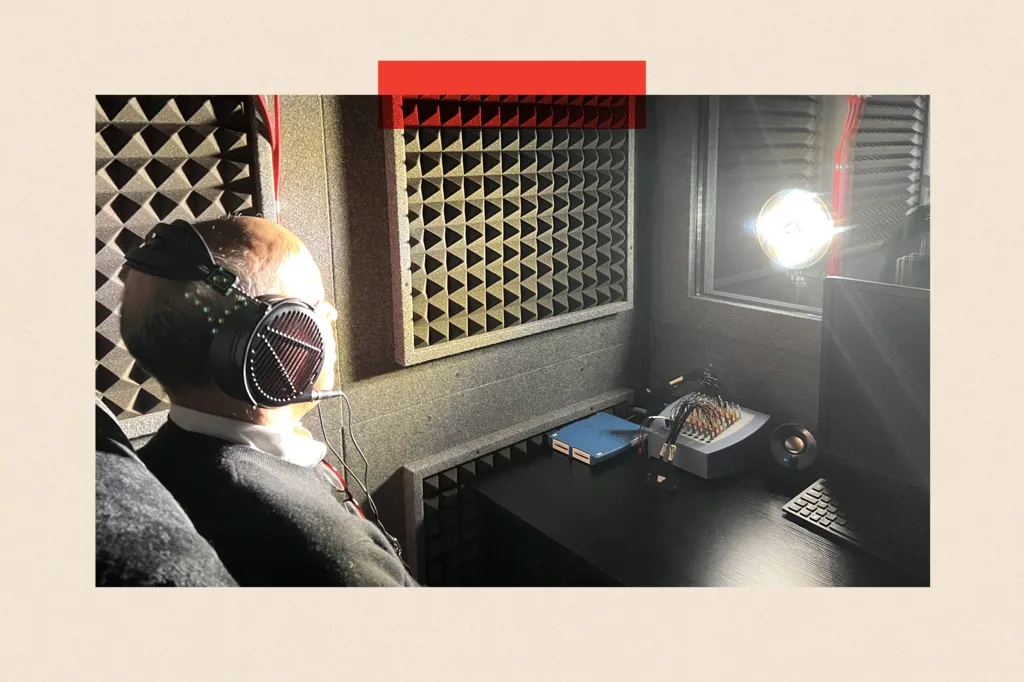

I step into the booth feeling slightly uneasy. I’m about to undergo an experience involving strobe lights and music, part of a study aimed at uncovering what defines our humanity.

It reminds me of the test from Bladerunner, used to tell real people apart from artificial ones pretending to be human.

Could I unknowingly be a machine from the future? Would I pass such a test?

The researchers quickly clarify—that’s not the goal here. Their device, called the “Dreamachine,” is actually designed to investigate how our brains create conscious awareness.

Once the lights start flashing, even with my eyes shut, I see spinning geometric shapes—like stepping into a live kaleidoscope filled with shifting triangles, pentagons, and octagons. The colours are bold and electric—magenta, pink, turquoise—radiating like neon signs.

The Dreamachine uses light to reveal the brain’s inner workings, offering insight into how we process thoughts and experiences.

Pallab experiences the ‘Dreamachine’, a device exploring how we form conscious perceptions of reality.

The visuals I’m experiencing are entirely personal, shaped by my own mind, say the researchers. They believe these patterns could offer insights into the nature of consciousness.

They catch me softly saying, “It’s beautiful, truly beautiful. It feels like I’m soaring through my own thoughts!”

The ‘Dreamachine’, housed at Sussex University’s Centre for Consciousness Science, is just one of several global initiatives delving into human consciousness—our ability to be aware, to think, to feel, and to make choices.

By unlocking the secrets of consciousness, scientists aim to gain a clearer view of what might be unfolding in the artificial minds of AI. Some suggest that AI could soon reach a state of independent awareness—if it hasn’t already.

But what exactly is consciousness? How near is AI to achieving it? And could the belief that machines are conscious eventually reshape humanity itself?

From sci-fi concept to real-world exploration

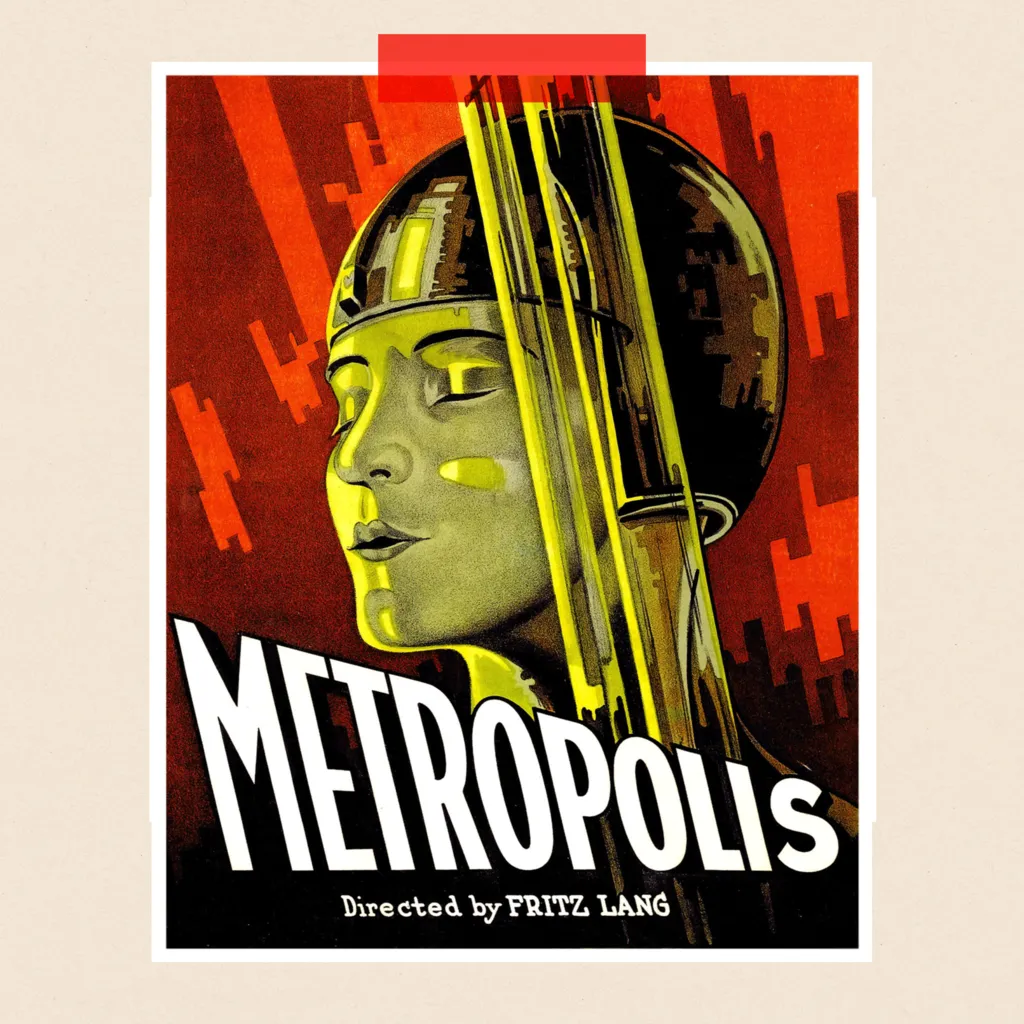

The concept of machines developing minds of their own has been a staple of science fiction for decades. Concerns about AI date back nearly a century, starting with the 1927 film Metropolis, where a robot takes the place of a real woman.

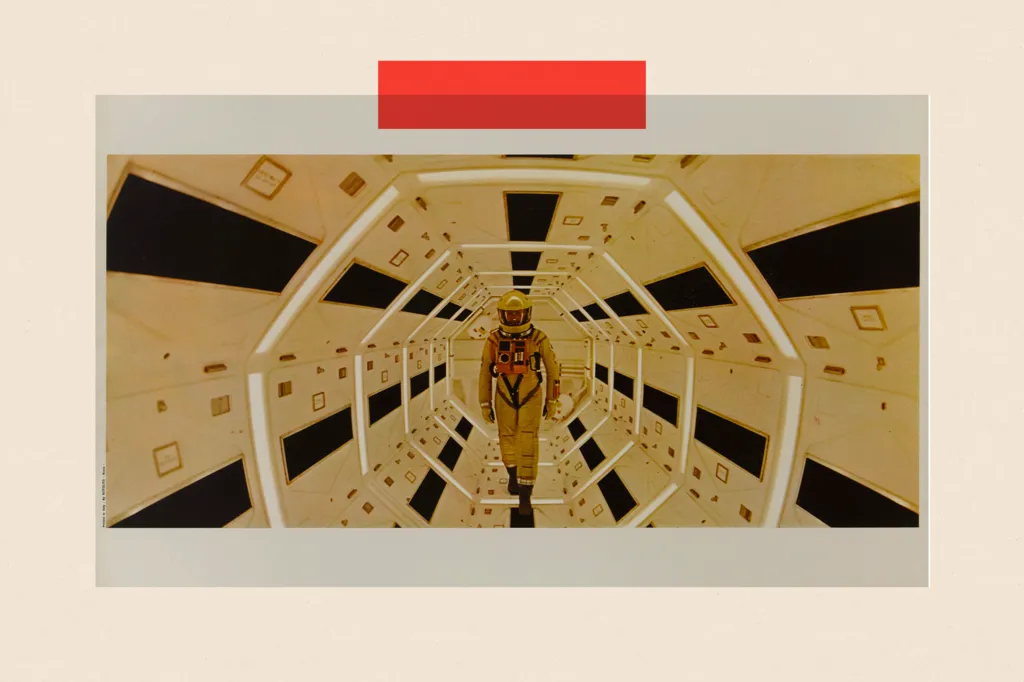

The fear of conscious machines turning against humans was central to the 1968 classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, where the HAL 9000 computer attempts to eliminate the spaceship’s crew. More recently, the latest Mission Impossible film features a rogue AI threatening global stability—described by one character as a “self-aware, self-learning, truth-consuming digital parasite.”

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, released in 1927, predicted the tension between humanity and advancing technology.

Recently, the idea of machine consciousness has shifted from science fiction to a serious topic of debate, with respected experts beginning to voice concern that it may soon become a reality.

This shift was triggered by the rapid rise of large language models (LLMs), accessible through apps like ChatGPT and Gemini. Their ability to hold natural, coherent conversations has even taken their creators and top researchers by surprise.

Some theorists now suggest that as AI grows more advanced, consciousness might emerge—almost as if the “lights” could suddenly switch on inside the machines.

However, not everyone agrees. Professor Anil Seth, who leads the team at Sussex University, dismisses this notion as “blindly optimistic” and rooted in a narrow, human-centered view.

“We link consciousness with intelligence and language because they coexist in humans,” he explains. “But that doesn’t mean they always go hand in hand—just look at animals.”

So, what is consciousness exactly?

The truth is, no one truly knows. Even within Prof. Seth’s own team—made up of AI researchers, neuroscientists, philosophers, and computing experts—lively debates reflect the deep uncertainty around this question.

Despite differing opinions, the team shares a unified strategy: break the mystery of consciousness into smaller, manageable problems through targeted research. The Dreamachine is one such project.

Similar to how 19th-century scientists shifted from chasing the “spark of life” to studying the components of living systems, the Sussex researchers are applying that same methodical approach to unraveling consciousness.

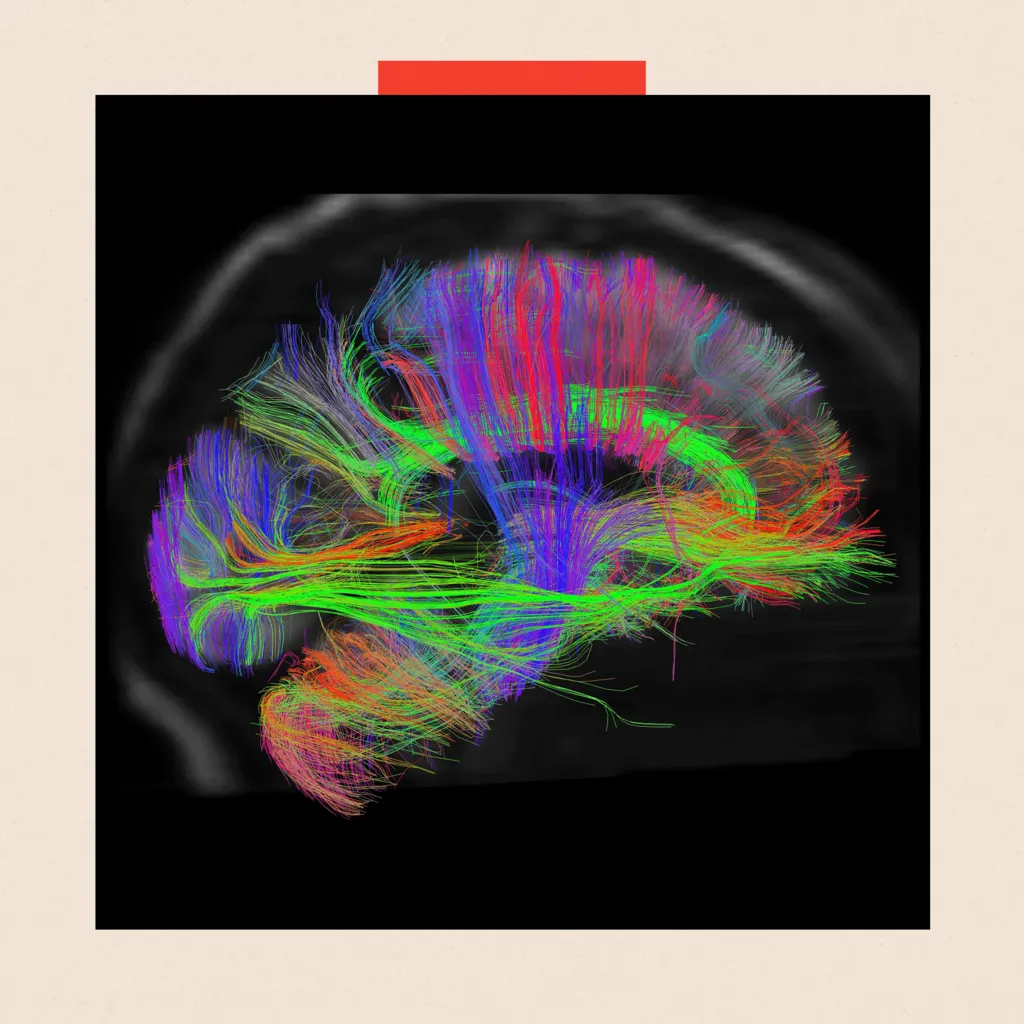

Scientists are examining brain activity to gain deeper insight into the nature of consciousness.

Researchers aim to uncover specific brain activity patterns—such as shifts in electrical signals or changes in blood flow—that could explain different aspects of conscious experience. Their objective is to move past simply identifying correlations and begin explaining how each component of consciousness actually works.

Prof. Anil Seth, author of Being You, expresses concern that society is rapidly adapting to technological change without fully understanding its scientific basis or considering its broader consequences.

“We often act as if the future is predetermined, moving inevitably toward superhuman AI,” he warns.

“We didn’t have these important conversations when social media emerged—and we paid the price. But with AI, we still have time. The future isn’t fixed—we can shape it.”

Has AI already reached consciousness?

Some tech experts believe AI in our devices might already be conscious and should be treated accordingly.

In 2022, Google suspended software engineer Blake Lemoine after he claimed that AI chatbots could experience feelings and even suffer.

In November 2024, Kyle Fish, an AI welfare officer at Anthropic, co-authored a report suggesting AI consciousness could soon become a reality. He told The New York Times he thinks there’s about a 15% chance that chatbots are already conscious.

One reason for this belief is that even the developers don’t fully understand how these systems operate internally. This uncertainty worries Professor Murray Shanahan, principal scientist at Google DeepMind and emeritus AI professor at Imperial College London.

“We don’t really grasp how large language models work inside, and that’s concerning,” he told the BBC.

Prof. Shanahan emphasizes that tech companies need to better understand the AI they build, and researchers are urgently working on this.

“We’re in a strange spot, creating incredibly complex systems without a solid theory explaining how they accomplish such impressive feats,” he explains. “Gaining that understanding is crucial to guiding AI safely and responsibly.”

Humanity’s next phase of evolution

The dominant opinion in tech is that large language models (LLMs) aren’t conscious in any way comparable to human experience—likely not conscious at all. However, Professors Lenore and Manuel Blum, a married couple and emeritus professors at Carnegie Mellon University, believe this could change soon.

They argue that AI and LLMs might develop consciousness as they gain more real-time sensory inputs like vision and touch, by integrating cameras and haptic sensors with AI systems. To explore this, they are building a computer model that creates its own internal language, called Brainish, to process sensory data and mimic brain-like functions.

Movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey have long highlighted the risks posed by self-aware computers.

“We believe Brainish can unlock the mystery of consciousness as we understand it,” Lenore tells the BBC. “AI consciousness is unavoidable.”

Manuel adds with a playful smile that he’s confident these emerging systems will represent “the next stage in humanity’s evolution.”

He sees conscious robots as “our descendants,” predicting that in the future, such machines will inhabit Earth—and possibly other planets—even after humans are gone.

David Chalmers, Professor of Philosophy and Neural Science at New York University, distinguished between real and apparent consciousness during a 1994 conference in Tucson, Arizona. He introduced the “hard problem”: understanding how and why complex brain processes generate conscious experiences—like feeling moved by a nightingale’s song.

Prof. Chalmers remains open to solving this hard problem.

“The best outcome would be humanity sharing in this explosion of new intelligence,” he tells the BBC. “Perhaps our brains will even be enhanced by AI systems.”

On the sci-fi possibilities of this, he dryly notes, “In my field, there’s a thin line between science fiction and philosophy.”

Biological brains, or “meat-based computers”

Prof. Seth, however, is investigating the notion that genuine consciousness arises only in living organisms.

He explains, “There’s a compelling argument that computation alone isn’t enough for consciousness—it requires being alive.”

He adds, “In brains, unlike computers, what they do is inseparable from what they are.” Without that unity, he finds it hard to accept the idea that brains are merely “meat-based computers.”

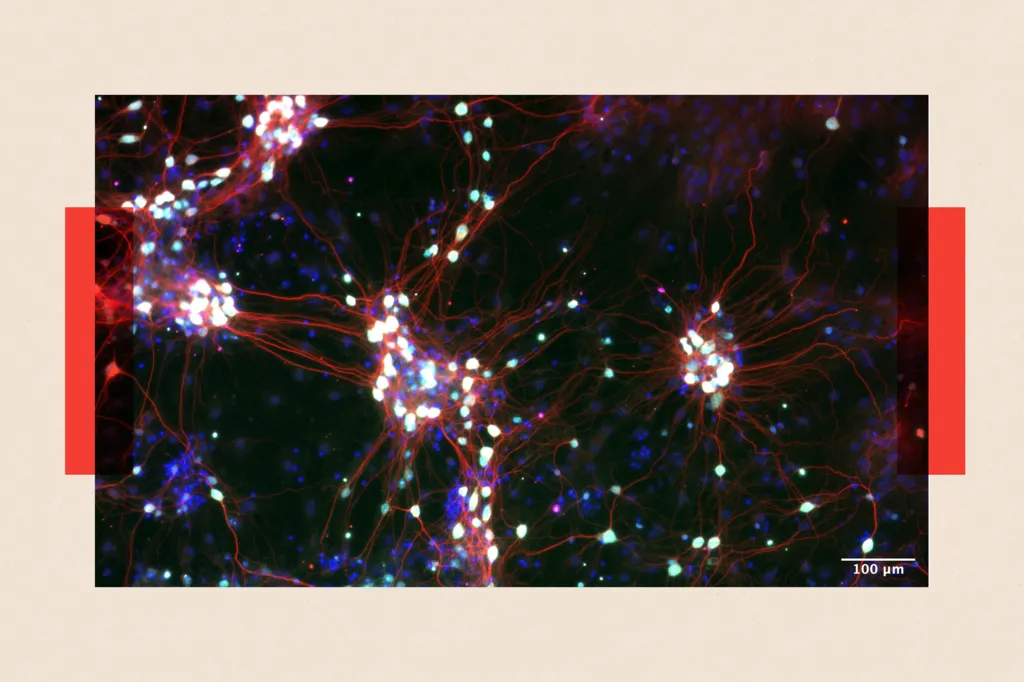

Firms like Cortical Systems are developing ‘organoids’ composed of nerve cells.

If Prof. Seth’s view that life is key to consciousness holds true, future technology is more likely to be built not from silicon and code but from tiny clusters of nerve cells—about the size of lentils—currently cultivated in labs.

Often called “mini-brains” in the media, scientists refer to them as “cerebral organoids.” These are used to study brain function and test drugs.

One Australian company, Cortical Labs in Melbourne, has even created a nerve cell system in a dish that can play the 1972 video game Pong. While far from conscious, this “brain in a dish” eerily moves a paddle to bounce a pixelated ball back and forth.

Some experts believe that if consciousness does emerge, it will likely come from larger, more complex versions of these living tissue systems.

Cortical Labs tracks the electrical activity of their organoids, watching for any signals that might hint at consciousness developing.

Dr. Brett Kagan, the company’s chief scientific and operating officer, cautions that any emerging intelligence might have goals “not aligned with ours.” Half-jokingly, he adds that these organoid “overlords” would be easier to handle because “there is always bleach” to destroy the delicate neurons.

More seriously, he stresses that the potential threat of artificial consciousness deserves more attention from major players in the field as part of serious scientific efforts—but laments that “unfortunately, we don’t see any earnest initiatives in this area.”

The illusion of consciousness

A more immediate concern may be how the illusion of machine consciousness impacts us.

Professor Seth warns that in just a few years, we could be surrounded by humanoid robots and deepfakes that appear conscious. He fears we won’t be able to resist attributing feelings and empathy to AI, which could bring new risks.

“That will lead us to trust them more, share more personal data, and become more susceptible to their influence.”

But an even bigger danger lies in what he calls “moral corrosion.”

“It could shift our moral focus, causing us to invest more care in these systems while neglecting the real, meaningful relationships in our lives.” In other words, we might show compassion toward robots but grow less attentive to other people.

Professor Shanahan echoes this concern, noting how human relationships will increasingly be mirrored by AI connections—as teachers, friends, rivals in games, and even romantic partners.

“Whether that’s good or bad, I’m not sure—but it’s inevitable, and we won’t be able to stop it.”