Secrets lie beneath the sands at the northern edge of the Rub al-Khali.

Covering an extensive area of 250,000 square miles (650,000 square kilometers), this vast desert in the Arabian Peninsula is often referred to as “The Empty Quarter.” To many, it appears desolate, characterized mainly by undulating ochre dunes.

However, artificial intelligence perceives differently. Researchers at Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi have developed an advanced method for exploring expansive, arid regions in search of potential archaeological sites.

Traditionally, archaeologists rely on ground surveys to locate areas of interest, a process that can be labor-intensive and challenging in harsh desert conditions. Recently, remote sensing techniques using optical satellite imagery, such as those from Google Earth, have become popular for scanning large areas for anomalies. Yet, in the desert, dust and sand storms frequently obscure visibility, and the patterns of dunes complicate site detection.

“We needed a tool to direct and refine our research,” explains Diana Francis, an atmospheric scientist and one of the project’s lead researchers.

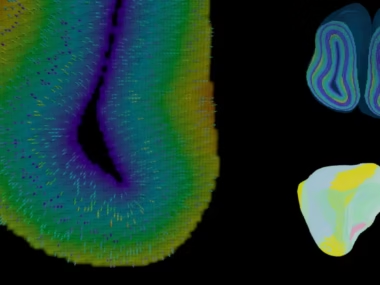

The team developed a machine learning algorithm to examine images gathered through synthetic aperture radar (SAR), a satellite imaging method that utilizes radio waves to reveal objects concealed beneath various surfaces, including sand, vegetation, soil, and ice.

While both SAR imagery and machine learning are established technologies—SAR has been used since the 1980s and machine learning is increasingly applied in archaeology—the integration of the two in this context is a groundbreaking approach, according to Francis, and to her knowledge, represents a first in the field.

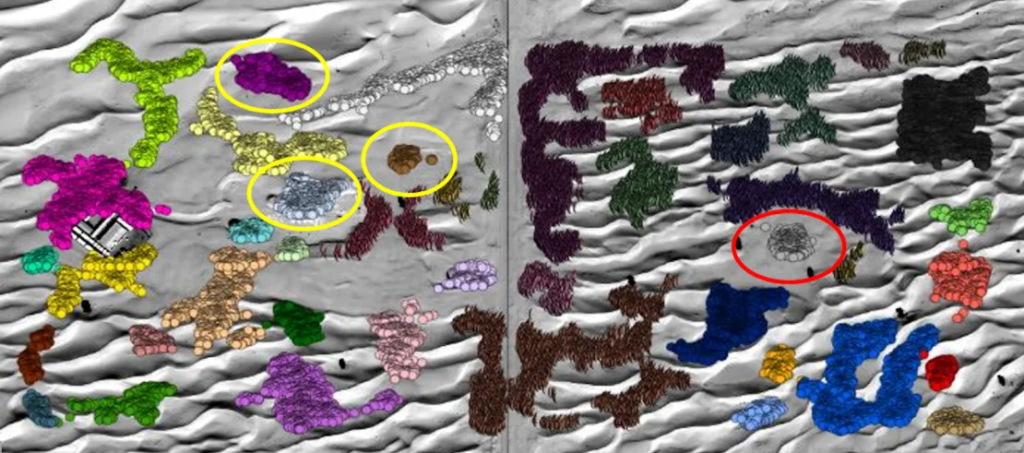

The satellite image depicts the Saruq al-Hadid site, highlighting the western zone where excavation has taken place (on the right) and the eastern zone, which remains unexcavated.

She trained the algorithm using data from an already recognized archaeological site: Saruq Al-Hadid, a settlement with evidence of 5,000 years of habitation that continues to be explored in the desert near Dubai.

“Once trained, it indicated other potential areas nearby that remain unexcavated,” Francis explains.

She notes that the technology is accurate to within 50 centimeters and can generate 3D models of the anticipated structures, providing archaeologists with better insights into what lies beneath the surface.

In partnership with Dubai Culture, the governmental organization overseeing the site, Francis and her team performed a ground survey using ground-penetrating radar, which “mirrored what the satellite measured from space,” she states.

Now, Dubai Culture intends to excavate the newly identified regions, and Francis is optimistic that this technique can help reveal more hidden archaeological treasures in the future.

Accelerating “Laborious” Tasks.

The use of SAR imagery in archaeology is not widespread due to its expense and complexity.

However, applying it to locate buried sites is “truly exciting,” remarks Amy Hatton, a PhD student at the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology, who is developing deep learning models to identify archaeological structures in northwest Saudi Arabia.

Hatton points out that by utilizing SAR imagery, which avoids issues with light scattering caused by dust particles, Francis and her team addressed technical challenges that make remote sensing difficult in desert environments.

Khalifa University is not the only institution employing artificial intelligence for site detection.

Amina Jambajanstsan, another PhD student at the Max Planck Institute, is using machine learning to accelerate the “laborious task” of examining high-resolution drone and satellite images for potential sites of interest. Her project, which focuses on medieval burial sites in Mongolia—a country covering over 1.56 million square kilometers, almost the size of Alaska—has revealed thousands of potential sites that she and her team would not have been able to locate through ground surveys.

Jambajanstsan acknowledges that while the costs and computational demands of SAR imagery may deter many researchers, this method is particularly beneficial for desert regions where other technologies struggle, and she would consider its use in the Gobi Desert in Southern Mongolia, where her “standard optical imagery” has not produced satisfactory results.

This labeled satellite image illustrates the locations of past and current excavations (indicated by the yellow circle) alongside the areas where the AI has predicted potential buried structures (marked by the red circle).

Human vs Machine.

Machine learning is increasingly being applied in archaeology, though not all researchers view it positively.

“There are two distinct belief systems,” explains Hugh Thomas, an archaeology lecturer at the University of Sydney and co-director of the prehistoric AlUla and Khaybar excavation project in Saudi Arabia. On one hand, some are embracing technological solutions like AI to locate sites; on the other, there are those who argue that a “trained archaeological eye” is essential for identifying structures.

While technology can aid in identifying and monitoring archaeological sites—especially those at risk due to land use changes, climate change, and looting—Thomas expresses caution regarding excessive dependence on it.

“I would prefer to use this type of technology in areas where the likelihood of archaeological sites is either very low or nonexistent, thus allowing researchers to concentrate on regions where we anticipate more discoveries,” he states.

Revealing the Past.

The true evaluation—and hopefully, validation—of the technology will take place next month when excavations commence at the Saruq Al Hadid complex, where only about 10% of the site has been uncovered over a 2.3-square-mile (6.2-square-kilometer) area, as reported by Dubai Culture.

If archaeologists uncover the structures predicted by the algorithm, Dubai Culture plans to utilize this technology to discover additional sites.

Francis and her team published their findings in a paper last year and are continuing to refine the machine learning algorithm to enhance its accuracy before broadening its application.

“The goal is to apply this technology in other regions, particularly in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and potentially deserts across Africa,” she explains.