China’s economy was initially expected to make a swift recovery in 2023 and continue its role as the primary driver of global economic growth. However, it faced significant challenges and stagnation, to the extent that organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) now describe it as a “drag” on global output.

Despite numerous issues, including a property crisis, sluggish consumer spending, and high youth unemployment, most economists anticipate that the world’s second-largest economy will achieve its official growth target of approximately 5% for the year. Nevertheless, this falls short of the 6%-plus annual growth rates seen in the decade before the Covid-19 pandemic. Looking ahead to 2024, concerns are growing, and there are worries that China might face prolonged economic stagnation.

Derek Scissors, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a center-right think tank, pointed out that the challenge in 2024 for the Chinese economy won’t be achieving GDP growth, which is likely to exceed 4.5%. Instead, the challenge lies in the fact that the only direction for the economy from there seems to be downward.

Without significant market reforms, China could find itself stuck in what economists refer to as “the Middle Income Trap,” a situation where emerging economies initially experience rapid growth, lifting them out of poverty, but then struggle to transition to high-income status.

For many decades following China’s re-opening to the world in 1978, it established itself as one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies. Between 1991 and 2011, it achieved an astonishing annual growth rate of 10.5%. Even after 2012, when Xi Jinping assumed the presidency, China’s economic expansion continued, albeit at a somewhat slower pace, with an average annual growth rate of 6.7% throughout the decade leading up to 2021.

However, there is growing consensus that the second half of the 2020s will witness a further deceleration in China’s economic growth. This expectation is primarily attributed to a correction in the troubled real estate sector and the challenges posed by demographic decline.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also expressed a more pessimistic outlook for China’s long-term economic prospects. In November, the IMF projected that China’s growth rate would reach 5.4% in 2023 but gradually decline to 3.5% by 2028. This decline is attributed to a range of factors, including weak productivity and an aging population, which pose headwinds to sustained economic growth.

“What’s different now?”

The Chinese economy, burdened by a range of difficulties, did not reach this state overnight.

Derek Scissors mentioned that during the global financial crisis in 2009, the previous administration under President Hu Jintao injected a significant amount of liquidity into the economy to stimulate growth. However, after coming to power in 2012, Xi Jinping’s government hesitated to curtail borrowing, leading to the accumulation of structural issues.

Logan Wright, who serves as the director of China markets research at Rhodium Group, concurred, explaining that China’s economic slowdown is fundamentally rooted in structural factors. This slowdown is a consequence of the conclusion of an extraordinary era of extensive credit and investment expansion over the past decade.

He further pointed out that China’s financial system will no longer be capable of generating credit growth at the same levels as in previous years. Consequently, Beijing will have significantly less influence over the direction of its economy compared to its past ability to control it.

What exacerbated the situation was Beijing’s steadfast commitment to a zero-Covid policy characterized by stringent lockdowns and an extensive crackdown on private businesses. These actions severely dented confidence and dealt a significant blow to the most dynamic segment of the economy.

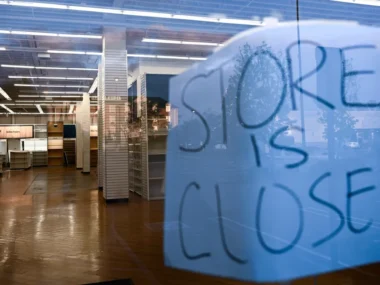

The repercussions of these policies are evident in the economic slowdown experienced this year. Weak consumer demand throughout 2023 has resulted in subdued consumer prices, raising concerns about the possibility of a deflationary cycle.

The crisis in the real estate sector has deepened further. Plummeting home sales have pushed even healthy developers like Country Garden to the brink of financial collapse. This crisis has spilled over into the extensive shadow banking sector, leading to defaults and sparking protests across the nation.

Local governments are grappling with financial challenges after three years of increased spending due to the Covid-19 pandemic and declining land sales. Some cities are unable to meet their debt obligations and have been forced to reduce essential services or curtail medical benefits for elderly citizens.

The severity of youth unemployment has reached a point where the government has ceased to release this data to the public.

Foreign companies have become increasingly cautious due to heightened scrutiny from Beijing and are consequently disinvesting from the country. In the third quarter, a key indicator of foreign direct investment (FDI) into China experienced a negative trend for the first time since 1998.

A survey conducted in September by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai revealed that only 52% of respondents held an optimistic view of their business prospects over the next five years. This represents the lowest level of optimism recorded since the survey’s inception in 1999.

Is China destined to follow a path similar to Japan’s?

As China’s economic growth begins to slow down, some economists have drawn parallels with Japan’s experience, which saw two “lost decades” of stagnant growth and deflation after its real estate bubble burst in the early 1990s.

However, Derek Scissors believes that China is unlikely to follow a similar trajectory, at least not in the immediate future. He suggests that the remainder of the 2020s will not resemble a lost decade, as Chinese GDP growth is expected to remain well above zero.

In the long run, though, China may face its most significant economic challenge in the form of demographics. In the previous year, China’s population declined to 1.411 billion, marking its first decrease since 1961. Additionally, the country’s total fertility rate, which represents the average number of babies a woman will have during her lifetime, plummeted to a record low of 1.09 last year, down from 1.30 just two years earlier. This means that China’s fertility rate is now even lower than Japan’s, a country that has long been recognized for its aging population.

A nurse provides care to a recently born infant at the Women and Children’s Hospital in Fuyang City, Anhui province, on August 8, 2022.

Demographic factors can exert a substantial influence on an economy’s capacity for growth. A reduction in the labor force, coupled with elevated healthcare and social expenditure, could result in a larger fiscal deficit and increased debt load.

A diminished workforce might also lead to a decline in savings, resulting in higher interest rates and a decrease in investment. Over the long term, this could lead to decreased demand in various sectors, including housing.

Derek Scissors pointed out that by the 2040s, population contraction could render overall economic growth unattainable. Without significant policy adjustments, China may not experience an economic rebound, and the 2030s could prove to be even more challenging than the 2020s.

Is it possible for Xi to chart a different path?

China’s leadership, who recently convened to discuss economic objectives and strategies for the upcoming year, has signaled their intention to increase fiscal and monetary support for the economy. They have also committed to enhancing “economic propaganda” and “public opinion guidance” in an effort to restore confidence.

Reports in Chinese media suggest that the government may once again target an economic growth rate of around 5% for the next year, which appears ambitious when compared to independent forecasts. The official target will be formally announced in March during China’s annual legislative sessions.

However, these measures are unlikely to address the underlying structural issues.

Julian Evans-Pritchard, Head of China Economics at Capital Economics, remarked that policymakers appear to believe that a combination of stimulus and a change in sentiment can put the economy on a more robust trajectory. Additionally, officials seem to hope that setting an ambitious growth target can help bolster confidence.

“While there is a degree of accuracy in this perspective, we believe that officials are downplaying the fact that China’s deceleration is predominantly of a structural nature and won’t be swiftly rectified.”

“The majority of this slowdown is a consequence of a fundamental decrease in productivity and income growth, rather than being a cyclical issue amenable to demand-side stimulus or similar confidence-boosting measures,” he stated.

If Beijing were to revert to its prior strategies, such as increased borrowing, it might manage to stimulate growth in 2024. However, Derek Scissors suggests that this would act as more of an economic pain-reliever than a permanent solution.